The Jews of Philadelphia: their history

from the earliest settlements

By Henry Samuel Morais

"As rich as

a Jew," that exaggerated saying so often heard, might well have been

substituted, in the American Revolutionary period, as well as in our own day,

by the remark: "As generous as a Jew." Apt illustration is found in the

careers of men who, though of foreign birth, and members of a religious

minority, proved more than loyal in times of need. Aaron Levy, Haym

Solomon, and others loaned extraordinarily large sums towards the cause of the

American colonists in their struggle for independence. But it is Haym Solomon

who deserves a golden page in the history of the United States; for his means

and his services were always at the disposal of the Government. He aided more

than a few statesmen while in distress; he gave plenteously to all; he

exhibited a charity and a philanthropy worthy of all praise.

Haym Solomon's name is on the first list of members of the Congregation

Mickv6h Israel, and in 1783 he served as a trustee of that religious

organization. That he subscribed liberal sums to the worship, goes without

saying. But this was a mere fraction of the total of his bounty. Haym

Solomon was not a native of America, having been born in Lissa, on the

Prussian side of Poland, in 1740, and descended from Portuguese stock. He came

to this country while young, and his patriotism in supporting the colonists

found him a prisoner in New York in 1775, while that city was in possession of

the British. The sufferings he experienced there, told on him subsequently,

notwithstanding that he succeeded in escaping and making his way to

Philadelphia. He had acquired wealth as a banker, and this he freely loaned to

Robert Morris, as the financier of the Revolution. The cause was assisted by

him to the extent of over $350,000. All the war subsidies obtained here from

France and Holland he negotiated, and sold them to American merchants at a

credit of two or three months, receiving for his commission but one fourth of

one per cent. At a certain time he was banker for the French Government. When

Continental money was withdrawn, thereby causing suffering among the poor of

this city, Mr. Solomon distributed $2,000 in specie to relieve distress.

Shameful to say, that, notwithstanding all claims, neither Haym

Solomon, who died in January, 1785, nor his heirs, have to this day, been

reimbursed by a Government that ought long since to have acknowledged its debt

to him who proved one of its main supports in the trying days of the

Revolution. A long array of recipients of Mr. Solomon's bounty might here be

presented. James Madison, afterwards the fourth president of the United

States, writes to Edmund Randolph: "I have for some time past been a pensioner

on the favor of Haym Solomon.'' And again: ''The kindness of our little friend

in Front Street, near the coffee house (Haym Solomon) is a fund that will

preserve me from extremities; but I never resort to it without great

mortification, as he obstinately rejects all recompense. To a necessitous

delegate he gratuitously spares a supply 'out of his private stock. " to

Thomas Jefferson, Arthur Lee, General St . Clair, General Mifflin, Edmund

Randolph, Robert Morris, and others, at home and abroad, were assisted by the

same generous hand. In fact, Haym Solomon's record was such in which he and

his co-religionists as well, have cause for just pride.

| |

|

| |

Haym

Salomon (ca. 1740 - 1785) |

|

|

by Bob Blythe

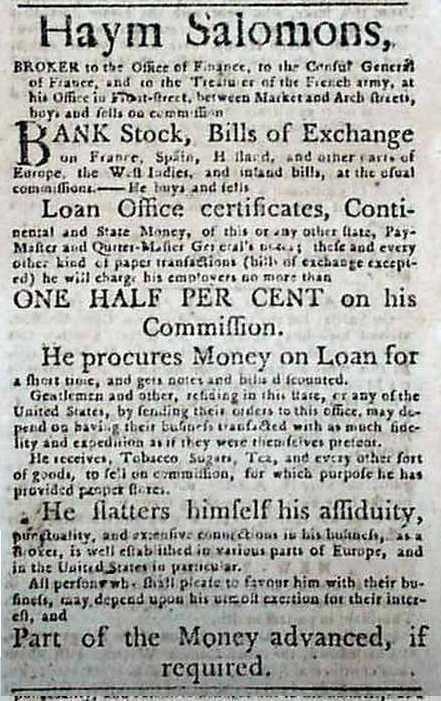

Salomon

(sometimes written as Solomon and Solomons in period documents) was a

Polish-born Jewish immigrant to America who played an important role in

financing the Revolution. When the war began, Salomon was operating as a

financial broker in New York City. He seems to have been drawn early to

the Patriot side and was arrested by the British as a spy in 1776. He was

pardoned and used by the British as an interpreter with their German

troops. Salomon, however, continued to help prisoners of the British

escape and encouraged German soldiers to desert. Arrested again in 1778,

he was sentenced to death, but managed to escape to the rebel capital of

Philadelphia, where he resumed his career as a broker and dealer in

securities. He soon became broker to the French consul and paymaster to

French troops in America. Salomon

(sometimes written as Solomon and Solomons in period documents) was a

Polish-born Jewish immigrant to America who played an important role in

financing the Revolution. When the war began, Salomon was operating as a

financial broker in New York City. He seems to have been drawn early to

the Patriot side and was arrested by the British as a spy in 1776. He was

pardoned and used by the British as an interpreter with their German

troops. Salomon, however, continued to help prisoners of the British

escape and encouraged German soldiers to desert. Arrested again in 1778,

he was sentenced to death, but managed to escape to the rebel capital of

Philadelphia, where he resumed his career as a broker and dealer in

securities. He soon became broker to the French consul and paymaster to

French troops in America.

Salomon arrived in Philadelphia as the Continental Congress

was struggling to raise money to support the war. Congress had no powers

of direct taxation and had to rely on requests for money directed to the

states, which were mostly refused. The government had no choice but to

borrow money and was ultimately bailed out only by loans from the French

and Dutch governments. Government finances were in a chaotic state in 1781

when Congress appointed former Congressman Robert Morris superintendent of

finances. Morris established the Bank of North America and proceeded to

finance the Yorktown campaign of Washington and Rochambeau. Morris relied

on public-spirited financiers like Salomon to subscribe to the bank, find

purchasers for government bills of exchange, and lend their own money to

the government.

From 1781 on, Salomon brokered bills of exchange for the

American government and extended interest-free personal loans to members

of Congress, including James Madison. Salomon married Rachel Franks in

1777 and had four children with her. He was an influential member of

Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel congregation, founded in 1740. He helped lead

the fight to overturn restrictive Pennsylvania laws barring non-Christians

from holding public office. Like many elite citizens of Philadelphia, he

owned at least one slave, a man named Joe, who ran away in 1780. Possibly

as a result of his purchases of government debt, Salomon died penniless in

1785. His descendants in the nineteenth century attempted to obtain

compensation from Congress, but were unsuccessful. The extent of Salomon’s

claim on the government cannot be determined, because the documentation

disappeared long ago.

In 1941, the George Washington-Robert Morris-Haym Salomon

Memorial was erected along Wacker Drive in downtown Chicago. The bronze

and stone memorial was conceived by sculptor Lorado Taft and finished by

his student, Leonard Crunelle. Although Salomon’s role in financing the

Revolution has at times been exaggerated, his willingness to take

financial risks for the Patriot cause helped establish the new nation.

To learn more:

Laurens R. Schwartz, Jews and the American Revolution: Haym

Salomon and Others (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 1987). |

Haym Solomon (or Salomon)

(1740–1785) was a Polish Jew who immigrated to New York during the period of the

American Revolution, and who became a prime financier of the American side

during the American Revolutionary War against Great Britain. He was born in

Leszno (Lissa), Poland, the son of a rabbi, and after leaving Poland, probably

in 1772 at the time of Polish partition,[1] immigrated to New York City circa

1775. In New York, he sympathized with the Revolutionary movement, and joined

the Sons of Liberty.

During the war, Solomon was twice arrested by the British; in 1776 he was

arrested as a spy and served as a German interpreter for the British

military's Hessian mercenaries. In 1778 Solomon was sentenced to death, but

escaped to Philadelphia,[2] where he acted as a broker for the Office of

Finance. Solomon worked extensively with Robert Morris, the Superintendent for

Finance for the Thirteen Colonies, and is mentioned nearly seventy-five times

in Morris' personal correspondence relating to the financing of the

Revolution.[3] Solomon also provided financial services to Continental

Congressional delegates James Madison and James Wilson,[4] and during the War

became the broker to the French consul, the treasurer of the French Army that

aided the Continental Army, and the fiscal agent of the French minister to the

United States.[5]

He was also active in Philadelphia's Jewish community and was a member of

Congregation Mikveh Israel. He died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at the age

of 45.

Early war

years

While in New York, he married Rachael Franks, the daughter of Moses Franks,

of a prominent colonial period Jewish family that included loyalist and

revolutionary sympathizers.[6] In 1776 he was captured by the British, but he

used his knowledge of German to convince his Hessian jailer to let him out. It

was during this period of incarceration that he contracted tuberculosis.

After this Solomon left New York, joining with the forces of the Continental

Army who were evacuating New York. He traveled south with George Washington's

Army and eventually settled in Philadelphia.

Commercial

accomplishments

Solomon was an astute merchant and auctioneer who succeeded in accumulating

a fortune, which he subsequently devoted to the use of the American government

during the American Revolution. For example, he personally supported various

members of the Continental Congress during their stay in Philadelphia,

including James Madison. Acting as the patriot

he was, he never asked for repayment. Solomon also negotiated the sale of a

majority of the war aid from France and Holland, selling bills of exchange to

American merchants.

He sold bills of exchange for the French, and those funds went to pay the

French military during their stay in Philadelphia. That is why some mistakenly

believe he was the paymaster-general of the French forces in the early years

of the United States.

Often working out of the "London Coffee House" in Philadelphia, he acted as a

broker for the Office of Finance. Solomon sold about $600,000 in Bills of

Exchange to his clients, netting about 2.5% per sale. During this period he

had to turn to his client in the Office of Finance, Robert Morris, when one

sale of over $50,000 nearly sent him to prison. Morris used his position and

influence to sue the defrauder and saved Solomon from default and disaster.

Activity

in Jewish community

Solomon was involved in Jewish community affairs, being a member of

Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, and in 1782, made the largest

individual contribution towards the construction of its main building. In

1783, Solomon and other prominent Jews appealed to the Pennsylvania Council of

Censors urging them to remove the religious test oath required for

office-holding under the State Constitution. In 1784, he answered anti-Semitic

slander in the press by stating: "I am a Jew; it is my own nation; I do not

despair that we shall obtain every other privilege that we aspire to enjoy

along with our fellow-citizens."

Death and

debts

Marker at Mikveh Israel Cemetery in Philadelphia.

After a solid career in Philadelphia, he saw opportunity in a different

state. Former client Robert

Morris tried to help him establish himself in New York. He died shortly

after he had decided to move back to city and become an auctioneer there.

His obituary in the Independent Gazetteer read, "Thursday, last,

expired, after a lingering illness, Mr. Haym Solomon, an eminent broker of

this city, was a native of Poland, and of the Hebrew nation. He was remarkable

for his skill and integrity in his profession, and for his generous and humane

deportment. His remains were yesterday deposited in the burial ground of the

synagogue of this city."

The gravesite of Haym Solomon is at Mikveh Israel Cemetery, located on the

800-block of Spruce Street, in Philadelphia. It is unmarked, but he has two

plaque memorials there. The east wall has a marble tablet that was installed

by his great-grandson, William Solomon, and a granite memorial is set inside

the gate of the cemetery. In 1980, the Haym Salomon Lodge #663 of the

fraternal organization B'rith Sholom sponsored a memorial in Mikvah Israel

Cemetery on the north side of Spruce st. between 8th and 9th Sts. in

Philadelphia. A large, engraved memorial marker of Barre Granite just inside

the cemetery gates was placed, inscribed, "An American Patriot".

When Solomon died, it was discovered he had been speculating in various

currencies and debt instruments. His family sold them at market rates, which

had greatly depreciated because of the weakened state of the American economy

in the 1780s. Subsequent generations misunderstood his truly patriotic actions

and appealed to Congress for more money, but were turned down twice. A myth

grew up that he had lent the young United States government about $600,000,

and at his death about $400,000 of this amount had not been repaid. This sum

was added to what he really had lent to statesmen and others while performing

public duties and trusts. Jacob Rader Marcus wrote in Early American

Jewry that the sum owed to Solomon was $800,000. That amount in 1785 is

equivalent in purchasing power to about $39,264,947,368.42 (using relative

share of GDP which indicates purchasing power) in 2005 US dollars.[8]

Myths and

historical legends

Commemorative marker at Mikveh Israel Cemetery

It is said that during the American Revolution, Solomon went to France and

raised an additional £3.5 million from the Sassoon and Rothschild banking

houses and families. However, David Sassoon had not been born yet, and would

later start up his counting house in Bombay, India, not France. Likewise, the

Rothschild family had not set up a bank in France yet either. At the time of

the Revolutionary war, the Rothschild's patriarch, Mayer Amschel Rothschild,

founder of the banking dynasty, was still in Hesse-Kassel (Hesse-Cassel),

loyally serving its prince, Wilhelm IX, who aided the British against the

Americans by supplying England with his Hessian mercenaries.

Solomon spoke eight languages. Supposedly, when he was in France, he passed

himself off as a French diplomat. Unfortunately, it does not conform to the

known facts. It is true his co-religionist, David Franks, did help Adams

negotiate loans from Holland. However, there is nothing in the record to show

that Solomon himself went to Europe for this purpose.

Solomon is sometimes alleged to have written the first draft of the United

States Constitution but the Philadelphia Convention occurred after his

death. Others have claimed that he designed The Great Seal of the United

States and that he included the Star of David, a Jewish symbol, above the

eagle's head. There is no documentary evidence to support this claim.

It is often said that Solomon lent hundreds of thousands of dollars to the

Revolutionary government, which never repaid him. In fact, the money merely

passed through his bank accounts.[9]

Honors,

testimonials and memorials

1975 United States postage stamp featuring Haym Salomon.

In 1893, a bill was presented before the 52nd United States Congress

ordering a gold medal be struck in recognition of Solomon's contributions to

the United States. In 1941, the writer Howard Fast wrote a book Haym Salomon,

Son of Liberty. In 1941, the George Washington-Robert Morris-Haym Solomon

Memorial was erected along Wacker Drive in downtown Chicago. In 1975 the

United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Haym

Saloman for his contributions to the cause of the American Revolution. This

stamp, like others in the "Contributors to the Cause" series, was printed on

the front and the back. On the glue side of the stamp, the following words

were printed in pale, green ink:

- "Financial Hero—Businessman and broker Haym Solomon was responsible for

raising most of the money needed to finance the American Revolution and

later to save the new nation from collapse."

The Congressional Record of March 25, 1975 reads, "When Morris was

appointed Superintendent of Finance, he turned to Solomon for help in raising

the money needed to carry on the war and later to save the emerging nation

from financial collapse. Solomon advanced direct loans to the government and

also gave generously of his own resources to pay the salaries of government

officials and army officers. With frequent entries of 'I sent for Haym

Solomon,' Morris' diary for the years 1781–84 records some 75 transactions

between the two men."

I

n 1939, Warner Brothers released Sons of Liberty, a short film starring

Claude Rains as Solomon. Hollywood film producer John C. W. Shoop, under

direction of MorningStar Pictures, is currently in production of a story of

the life and times of Haym Salomon called On The Money.

In World War II the United States liberty ship SS Haym Solomon was named in

his honor.

Footnotes

- ^ Milgram,

Shirley. ""Mikveh

Israel Cemetery."". USHistory.org. Retrieved on 2008-06-26.

- ^ "[ttp://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/haym_salomom.html

Haym Solomon]". National Park Service, US Department of the Interior.

Retrieved on 2008-06-26.

- ^ Wiernik,

Peter. History of the Jews in America. New York: The Jewish Press

Publishing Company, 1912. p. 96.

- ^ Wiernik,

Peter. History of the Jews in America. New York: The Jewish Press

Publishing Company, 1912. p. 95.

- ^ Wiernik,

Peter. History of the Jews in America. New York: The Jewish Press

Publishing Company, 1912. p. 95.

- ^ Peters, p.

12

- ^ On June 17,

1980 the Philadelphia public was advised of the fact in the Philadelphia

Morning Inquirer, complete with a background story and photograph of the

event.

- ^

[Used 1790 - 2005 as the calculator only goes to 1790...]

- ^

Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past, by

Roy Ronsezweig, in The Journal of American History Volume 93,

Number 1 (June, 2006): 117-46. The sentence is between note 30 and 31

References

- Amler, Jane Frances. Haym Solomon: Patriot Banker of the American

Revolution.

ISBN 0-8239-6629-1

- Hart, Charles Spencer. General Washington's Son of Israel and Other

Forgotten Heroes of History.

ISBN 0-8369-1296-9.

- Peters, Madison C. Haym Solomon. The Financier of the Revolution.

New York: The Trow Press, 1911.

- Russell, Charles Edward. Haym Solomon and the Revolution.

ISBN 0-7812-5827-8.

- Schwartz, Laurens R. Jews and the American Revolution: Haym Solomon

and Others (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 1987).

- Wiernik, Peter. History of the Jews in America. New York: The Jewish

Press Publishing Company, 1912.